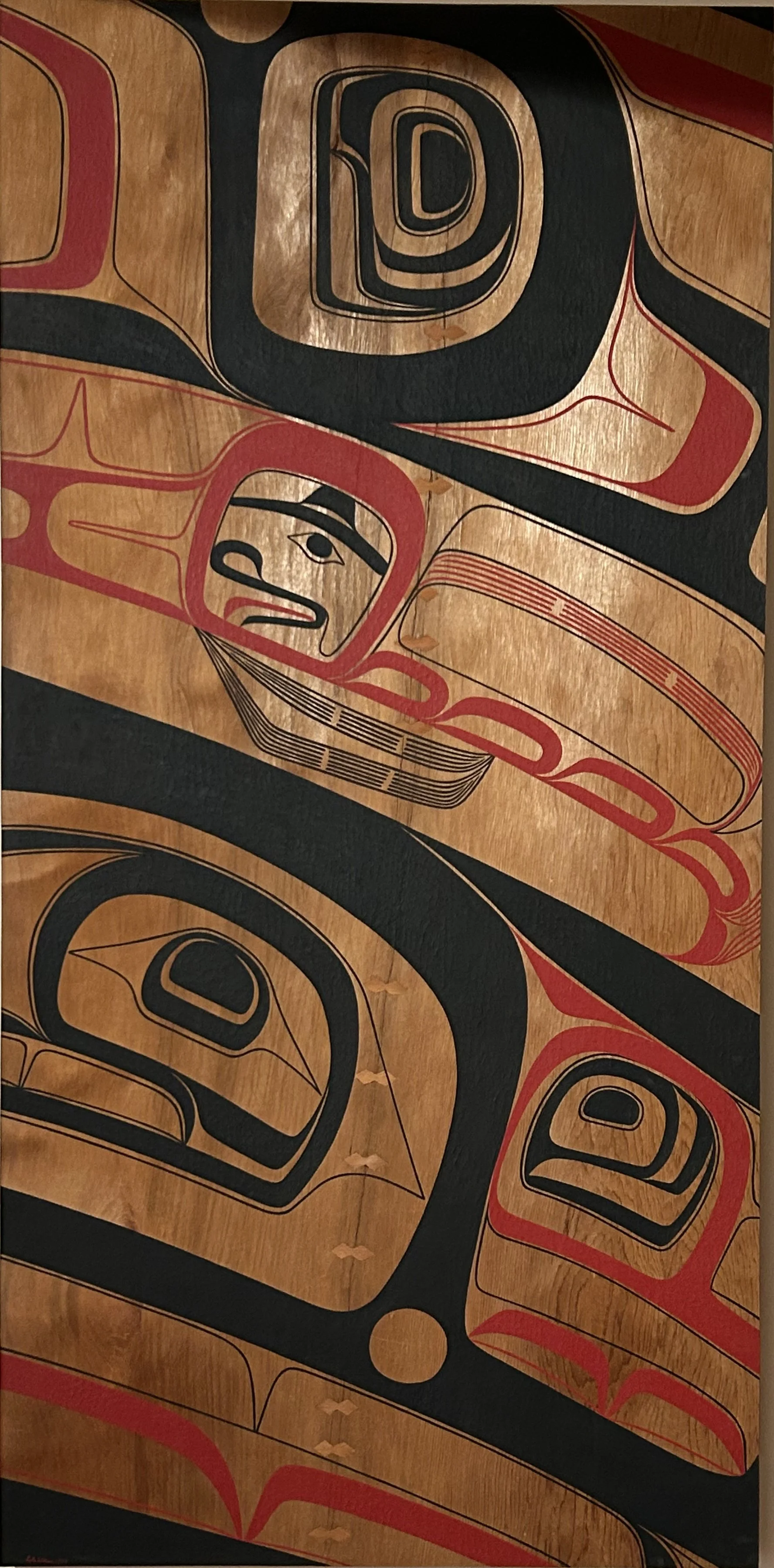

Northwest Coast Dagger

Contrary to what many non-Indigenous writers say about the role of warfare in Northwest Coast society, it was not endemic, but rather undertaken primarily in times of climate change when famine plagued peoples whose economy was marginal. As people left their territories in search of food, they put pressure on the borders and livelihoods of neighbouring peoples.

The peak periods of warfare recorded in Northwest Coast oral histories have been dated to 4200 BP, 3000 BP, 1500 BP and 500 BP, all times of world-wide climate cooling in the north and drought in the south. The most recent period of warfare – before “contact”- was during what is called the Little Ice Age in the 17th to 19th centuries.

By this time, a sophisticated system of trade between house groups within Northwest Coast nations was in place, and wealth was not only derived from house group and tribal territories, but also from trade alliances and control of trade routes. So it was when the climate changed in the 17th century, travel beyond one’s nation was well-established, and warfare practices and technologies spread among the nations of the Northwest Coast, with fortified sites, man to man combat, armour, battle headdresses, spears, and, with the arrival of metal, daggers.

Artworks by Haisla Artist Lyle Wilson

In the 1950s, Northwest Coast First Nations culture was increasingly at risk in Northern British Columbia as the forced removal of children from their families and communities broke the lines of cultural transmission. Children were removed to residential schools where thousands of years of their cultural knowledge was systematically supplanted by that of the newly arrived Europeans.

Before this, children had always learned from their parents, their aunts and uncles, and their grandparents, and from the experts among them, such as the artists and shamans. The culture had stayed alive for millennia, passing from one generation of children educated and trained in this way to the next.

2024 Donation to The Museum of Northern BC from Philanthropist Gary Bell of Vancouver

This delicately carved and painted clapper was collected by R.J. Dundas at Metlakatla in 1863. Clappers

are musical instruments used in ceremonial events on the Northwest Coast. The clapper may have been

carved specifically for sale or may have been in use by the Tsimshian before it was sold. The entire

Dundas collection was sold at Sotheby’s in 2006 and this clapper was eventually resold to Gary Bell, who

very generously donated it to the Museum of Northern BC in 2024. He previously also donated several

bowls from the collection.

The artwork is classic Tsimshian and the painting, dashing and carving is very meticulous. The technical

ability to carve the wings and tail as one piece and hollow it out at the same time is amazing. The binding

is original and intact.

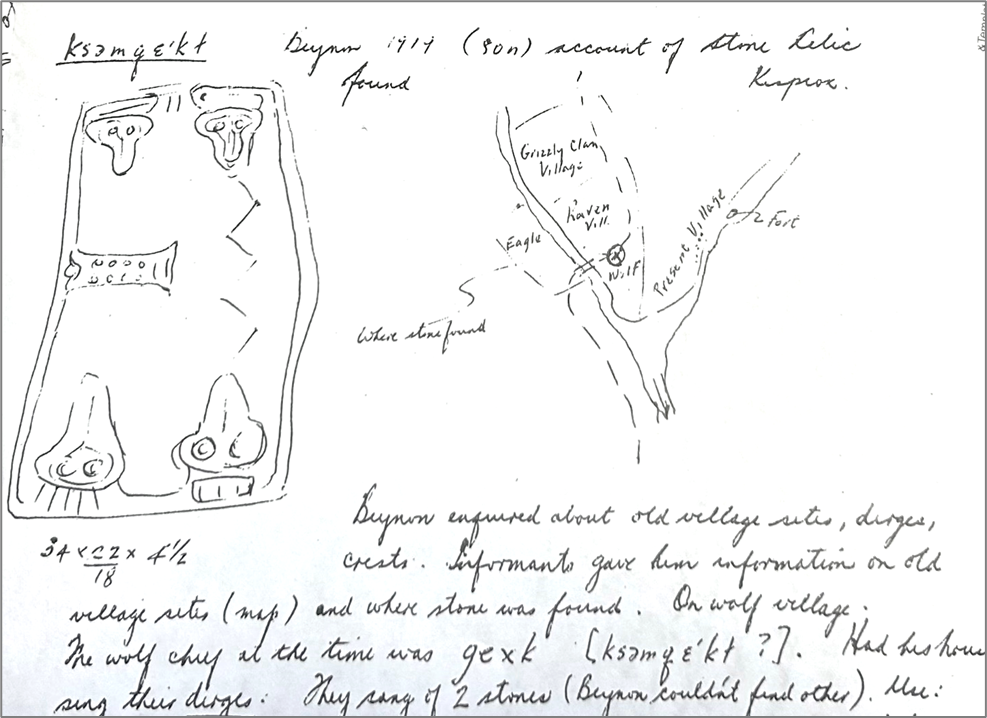

Plaster cast of a prehistoric carved stone slab found at the confluence of the Kispiox and Skeena Rivers.

The original carved stone is said to have been collected by Harlan I. Smith in 1919, but it’s location today is unknown. William Beynon made a sketch of the carving and of the location where it was found - in the ground at the site of the ancient Wolf village of the Git’anspayaux (Kispiox people). The carved images are said to possibly represent the Dragonfly one of the crests of a Kispiox Wolf chief. The cast was donated to the Museum of Northern BC for safe keeping in 1925 and remains in the Museum’s collection.